The Benefits of a Mature Hedgerow

The hedgerow is recognizable as a common feature throughout the countrysides of the United Kingdom, Ireland, and throughout Massachusetts, here in the states. Hedgerows are roughly defined as a contiguous line of shrubby plant material, mixed with tree species.

Benefits of a Mature Hedgerow

Example of a hedgerow

According to data from a 2007 survey conducted by Hedgelink UK, an organization based out of the united kingdom, there are approximately 250,000 miles (402,000 km) of managed hedgerow, with another 60 or so thousand that have become feral. In the same report, there is mention of mature hedgerows that are estimated to be around 800 years old. This clearly shows that hedgerows have been a common tool in the development of sustainable/regenerative land stewardship for a significant period of time. As a major component of a region’s green infrastructure, this type of longevity becomes critical for maintaining regional diversity of flora and fauna, healthy soils, and high yields.

European hedgerows provide multiple benefits to the land and many of its inhabitants.

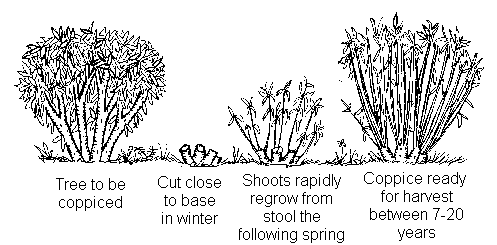

As the forests were cleared by farmers to create arable land, hedgerows became the proxy boundary lines. Hedgerows played a pivotal role in providing green infrastructure rich in renewable resources. The most of obvious being it kept animals on the property, as well providing a regenerative source of firewood, animal fodder and building materials. Coppicing of the trees within the hedgerow, the practice of cutting relatively young wood back down to ground level, is still a common practice for creating a reusable fuel source.

Diagram illustrating the coppicing cycle over a 7- to 20-year period Creative Commons

The number of data driven studies around the benefits of the hedgerow are extremely limited. With the overwhelming majority of material about hedgerows and the benefits thereof being anecdotal, the technique has been open to debate around the efficacy of the practice. This lack of data was recently addressed in a 2013 paper published by two scientists from the Department of Environmental Science, UC Berkeley.

Blackberries, like this one in a Devon hedgerow, are excellent because they provide multiple yields: fencing, food, habitat and medicine. Photo CC Miles Wolstenholme

The study focused on agricultural land in the San Joaquin Valley of central California. The researchers were looking to determine if there was evidence of a positive correlation between increased biodiversity of beneficial flora, pollinator species and managed hedgerows in agricultural zones. What the data demonstrated is that among various bee species and hover flies, there was a marked increase in species density including uncommon species, for distances up to 100 meters from the hedgerows. This is great production news not only for farmers but for the home gardener with fruit trees, ornamentals, and herbs as well.

Pollinator species, bees, flying insects, butterflies, moths, birds, are essential for crop yields.

Crop yields relate to the homeowner directly in the number and vigor of flowering plants, the amount of peaches that set in the home orchard, etc. The more flying things the more flowering things; it’s a positive feedback loop. A major challenge for developing healthy soils within the confines of the urban zones is the problem of how to mitigate the migration of unwanted inorganic fertilizers or compounds onto the property. Hedgerows can be put to work by acting as an organic screen, disrupting sheet flow and filtering the water as it passes through the woody and leafy material, and then again within the soil via a complex network of root tissue. The process of remediating the water quality is enhanced even further when we look at the biological processes happening in the soil.

A diversity of plants helps attract a diversity of pollinators.

A diversity of plants helps attract a diversity of pollinators.

Generally speaking, perennial plants prefer to have the soil dominated by a fungal soil biology. Fungus, specifically the unseen parts of the mushroom, the mycorrhizae, have the capacity to breakdown a variety of contaminants and lock them up in an inert state within the soil. This organic process has been documented for a number of years now, and in a variety of contexts. The mycologist Paul Stamets is widely recognized as a pioneer in this work, and has been directly responsible for a number of bioremediation programs throughout the world. Mulching around our perennial plants, with prunings and woody materials, provides the food sources for the fungal communities we want to have established within the root zones of our hardworking hedges. Here we see that mulching serves with a stacked functionality of mitigating the damaging effects of desiccation, loss of moisture to wind and sun, as well as fostering the nutrient requirements for the mycorrhizal community. Hedgerows compound this water conservation component by serving as windbreaks. Much like they break up the sheet flow of sediment harboring runoff, they alter the movement and strength of prevailing wind patterns, allowing for the creation of more hospitable micro climates. Another aspect of the hedgerow which can be a significant bonus in our attempts to minimize the negative impact of our personal footprint, is its usefulness in providing a frontline defense against the loss of topsoil. In the same way that the hedgerow physically inhibits the movement of contaminants onto our properties, it prevents the further loss of already depleted soils from leaving our sites. Regardless of what our choices for a landscape design may be, ornamental, edible, etc., this is of major consequence to the long term health of the site. All of the composting, worm castings, compost teas and mulch that we lay onto our soils and plant tissues, amount to very little if we don’t sequester these nutrient sources on site, and add them to the soil profile. This plays into our local environmental footprint by preventing sediment from entering the sewer system and ultimately our local waterways and the ocean. The recurring algae blooms, poor water quality warnings and beach closures are a direct result of sediment from our roads and neighborhoods making its way into our coastal waters. Scripps Institute of Oceanography published a report in September of last year demonstrating how sediment deposits have affected and can affect our coastal zones. Carbon farming has become an often discussed concept with numerous organizations conducting carbon sequestration research aimed at reducing the global volumes of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere. Hedgerows have been demonstrably useful in the carbon sequestration formula.

Soil has the potential to sequester three times the volume of carbon as compared to plant tissue, and twice the volume of carbon as can be sequestered in the atmosphere.

Organic material, trees, shrubs, grasses, intake carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and through the process of photosynthesis, the carbon dioxide is broken down allowing the carbon to become a part of the plants tissue. As plants die or shed tissue, either through natural processes or mechanical pruning, the carbon that was stored in the plant material now enters the soil strata. Data from the above linked paper published by The Organic Research Center detailing the carbon sequestration potential of hedgerows, shows that soil has the potential to sequester three times the volume of carbon as compared to plant tissue, and twice the volume of carbon as can be sequestered in the atmosphere. How that breaks down on a practical home scale is that the more plant material we have on our properties, drought tolerant species of trees, shrubs, flowers and grasses, the more potential carbon dioxide can be placed into our soils via pruning, root die off, mowing, etc. With that in mind, now when we prune or mow and we allow the organic material to remain on site, not only are we added to the organic composition of our soils, expanding upon the water conserving potential, but we’re contributing to the carbon offset of our modern, carbon-heavy lifestyles. Mind you, this isn’t to declare a carbon neutral option to a resource consuming society. The reality is that all aspects of our modern lifestyle, from our cars, to our computers, to our agriculture, to the jeans we wear and on down the line, we are belching carbon dioxide, and other compounds, into the atmosphere, and clearly we aren’t stopping any time soon. However, when understanding the complexity of our impact on the environment that we most directly relate with, our homes, our daily routes of travel and so forth, and choose to make the “Environment” not something abstract and nebulous, we can make wiser choices without mistakenly assuming the logical fallacy that we need to regress to paleolithic lifestyles to provide, at the very least, a viable resource future for the denizens of the society who will follow behind us. Keep in mind, our landscapes are a piece of the wider habitat that we all live within. In viewing the single family landscape as something that does not exist in a vacuum, it becomes an organism that reflects the health of the wider biome it resides in as an integral member of the “Environment”. This isn’t magical thinking, but science based with a track record of demonstrable success.

FREE REPORT - 8 Ways To Save Water In Your Landscape

Learn the techniques we use on a daily basis to maximize your water budget.